God doesn’t promise that He’ll only ask you for the sacrifices you agree with and understand. – Eve Tushnet

The nuns taught us there are two ways through life: the way of nature and the way of grace. You have to choose which one you’ll follow. Grace doesn’t try to please itself; accepts being slighted, forgotten, disliked; accepts insults and injuries. Nature only wants to please itself. – Terence Malick, Tree of Life

In paragraph 265 of Amoris Laetitia, Pope Francis teaches:

We have to arrive at the point where the good that the intellect grasps can take root in us as a profound affective inclination, as a thirst for the good that outweighs other attractions and helps us to realize that what we consider objectively good is also good “for us” here and now. A good ethical education includes showing a person that it is in his own interest to do what is right. Today, it is less and less effective to demand something that calls for effort and sacrifice, without clearly pointing to the benefits which it can bring.

The basic message is traditional. Morality involves rational pursuit of the good. This is so by definition because humanity was created with a desire for happiness (which, as St Augustine beautifully explains in his Confessions, can ultimately be satisfied only by God) – or, as ancient Greeks called it, eudaimonia (“flourishing”). Whatever we choose, we choose because we judge, rightly or wrongly, that it will contribute to eudaimonia. As Herbert McCabe puts it:

Living well means doing good because you want to do it, because you have become the kind of you that just naturally wants to do this.

The Church believes her rules surrounding sexual behaviour are not arbitrary. The goods indicated as desirable by Church teaching are (in the Holy Father’s words) good “for us,” given the way our nature was created. Pope Francis is restating the Church’s belief that her teachings on sex concern natural law, not eccelesiastical policy.

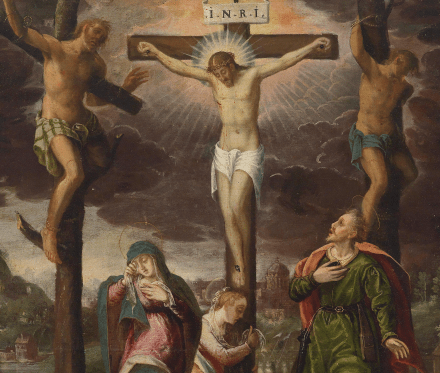

But paradigms of moral behaviour in Scripture often cannot be understood within the context of an ethic solely focused on the pursuit of eudaimonia. In the Garden of Gethsemane, Christ prays:

Abba, Father … all things are possible for you. Take this cup from me. Yet not what I will, but what you will. (Mark 14:36)

Christ, God and man, had two wills and two intellects (human and divine). His prayer indicates the desire of his (human) will is at odds with the Father’s desire. This suggests that Christ’s human intellect, in itself, could not grasp that his Passion was “in his own interest.” If it had grasped this, even his human will would have desired to undergo the Passion, since the will naturally desires what the intellect grasps as good.

St Augustine says that by praying as he did, Christ “shows Himself to have willed something else than did His Father.” St Thomas Aquinas explains this by arguing that although Christ’s “will as reason” always “willed the same as God,” in his “rational will considered as nature, Christ could will what God did not.” What is important to note is that even the human will of Jesus, although it never experienced disordered affection, cannot be said to have had a “profound affective inclination” toward his proper good at all times; nor can his human intellect, in itself, have been capable of completely comprehending that good, even though Christ’s human intellect (unlike ours) knew everything possible for a human intellect to know.

You must be logged in to post a comment.