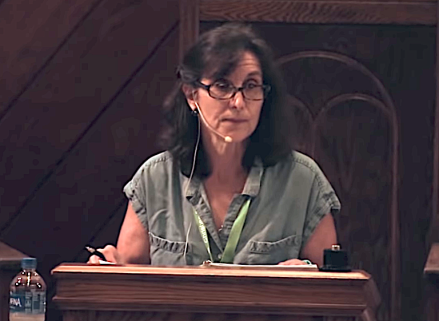

Many of our readers are likely familiar with Rosaria Butterfield, who has a powerful testimony being converted to Christianity while being a professor specializing in queer studies. Although I’ve had certain disagreements and frustrations with her, she had always struck me as a compassionate, honest, and fair person.

For this reason, I was surprised when I recently happened upon this video of Rosaria Butterfield talking to a Presbyterian Church in America (PCA) church. Starting around the 53 minute mark, she made slanderous statements about several groups near and dear to me—the PCA, Reformed University Fellowship, and Spiritual Friendship. I was surprised by the degree to which she misrepresented these groups, because I was expecting better from her.

For example, at one point Butterfield stated,

Especially today, and I know I’m speaking in a PCA church, so I understand the stakes of this, but especially today, the PCA is smitten in a stupid way, and I’m using a hard word, very stupid way, and to their shame, to the gay Christian movement, both A and B.

She also added, “RUF, I’m talking to you here.”

“A and B” refer to the “sides” of the debate on gay relationships and Christianity. This terminology was originally developed at Bridges Across the Divide and later popularized at the Gay Christian Network. Side A is the belief that the sex of the people in a sexual relationship has no bearing on the morality of the relationship, while side B (the view espoused by the writers on Spiritual Friendship) is the belief that the only appropriate context for sex is marriage between a man and a woman. Rosaria’s claim here is that both sides, including in particular the revisionist “side A,” are well-represented within PCA and RUF leadership. This is an extraordinary claim. The doctrinal statements that PCA and RUF pastors and elders uphold take the “side B” view, as Butterfield herself does.

I am fairly familiar with how the PCA is approaching sexuality. Over the past few years, I’ve been a member in good standing of two PCA churches in fairly liberal college towns (Chapel Hill, NC and Madison, WI). I’ve been close with a pastor at each church, and paid some attention to denominational politics. I’ve had a number of friends studying at Covenant Seminary. In all these settings I’ve had numerous discussions regarding sexuality.

And while I never participated at RUF as a student (having gone to a Christian university for my undergraduate work), I’ve known quite a few students and alumni from the group. Several of my friends have gone on to do RUF internships or to go on staff with RUF. And the work of RUF matters to me, to the point that RUF is second only to my local church in terms of how much money I’ve given.

My experience further solidifies my belief that Butterfield’s claim is patently false. I see no evidence that leadership of RUF and the PCA are embracing a “side A” perspective at all. Perhaps Butterfield is just talking about laypeople in the pews or students who attend RUF events, rather than leadership? But it’s not fair to the PCA or to RUF to blame them for the culture in which they’re trying to do faithful Christian ministry. Unless Butterfield can provide substantial evidence to back up her claim, her statements about RUF and the PCA amount to slander.

She also made some harsh and unfair criticism of Spiritual Friendship:

Or hey, I could go “side B” with Wesley Hill and the Spiritual Friendship gang, where I would learn that my sexual desires for women were actually sanctifiable and redeemable, making me a better friend to one and all, but for the sake of Christian tradition, I should not act on them. Well, if you haven’t figured out by now, I was raised on the wrong side of the tracks. So let me tell you right here, that telling someone like me that I am to deny deep desires because of Christian tradition is simply absurd. Christian tradition is no match for the lust of the flesh.

I think that sexual strugglers need gay Christianity and all of its attending liberal sellouts, including the side B version, like fish need bicycles, to refresh an old feminist slogan. Gay Christianity, touted as the third way for those churches and colleges, is a poor and pitiful option to give someone like me. And while some people see a world of difference between between acting on unholy desires and simply cherishing them in your heart, our Lord would say otherwise. If anger is murder and lust is adultery, then the differences that separate the factions of gay Christianity, the differences between Matthew Vines and Wes Hill, take place on a razor’s edge, not a chasm.

This represents a very serious misunderstanding of what Spiritual Friendship promotes and teaches. Spiritual Friendship has always defended the orthodox Christian teaching on sexual ethics (see here, here, here, here, and here, for a few examples).

Now I do want to acknowledge that much of Butterfield’s view is probably from this post by Wesley Hill. At least Ron Belgau and I have long had certain concerns about this and some of Wes’s other writing. Primarily, we thought it was too ripe for misinterpretation and needed more explicit theological development. We also realized it could come across to our critics as viewing temptation or sin too positively, or could encourage sloppy thinking that would actually cause some of our readers to view temptation or sin too positively. Ron has pushed back against this some and attempted to provide a more rigorous reflection on some of the issues in Wes’s “Is Being Gay Sanctifiable?” post.

To be honest, our readers really need a much fuller explanation of what we’re trying to say than can feasibly be done in this blog post. And we need to figure out within Spiritual Friendship to what degree there is agreement among the contributors. Ron and I have started discussing how to do a longer series of posts to discuss some of the questions at hand, but will want to take some time to develop it carefully. But in immediate response to this video, I want to clarify what we are not saying.

I want to be clear: we are not saying that as long as you’re not having sex, you’re fine. None of us would say that viewing pornography or entertaining lustful fantasies, for example, are morally acceptable, even if those are sins that some of us (like many other Christians) struggle with. We take seriously Jesus’s teaching that lust is adultery.

Additionally, we are not saying that desires to have sex with someone of the same sex are sanctifiable or something to be “cherished.” Wesley Hill was trying to describe aspects of his experience other than the desire for sex, and as I said, the point really demands a more rigorous explanation than he has yet provided.

Another strange notion in Butterfield’s presentation of our view is that we just pursue celibacy “because of tradition.” This isn’t really how we would describe it. We try to avoid gay sex because we believe it’s what God wants of us. The reason I haven’t pursued a sexual relationship with a male isn’t just because I want to respect tradition. It’s because I love Jesus. I believe that pursuing that kind of relationship, as with any other sin, would hurt my relationship with Christ. As a Protestant, the value of tradition for me is that it helps me understand what God has taught in Scripture. But Scripture is my ultimate authority, because it’s where I believe God has infallibly spoken.

And to deal with the sin in my own life, what I need is the Gospel, discipleship, and the power of the Holy Spirit. It’s certainly not just a matter of me doing the right thing in my own power because I trust tradition. We’re pitting the Gospel, discipleship, and the Holy Spirit, rather than tradition, against the lust of the flesh. I’m baffled why Rosaria Butterfield seems to think we claim otherwise.

I hope that Rosaria Butterfield, and anyone else who has seen the video, can come to a better understanding of where the PCA, RUF, and Spiritual Friendship stand. And I think Rosaria Butterfield owes these groups an apology for slandering them.

You must be logged in to post a comment.