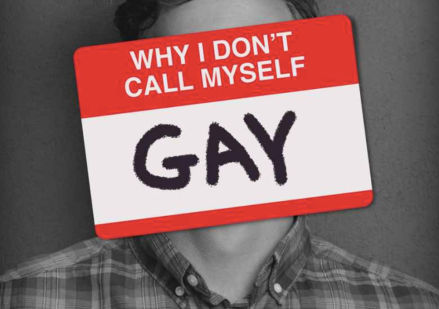

One of the most consistent criticisms of Spiritual Friendship by those associated with Courage has been our use of language, particularly the word “gay.” One of the earliest criticisms was Dan Mattson’s July, 2012 First Things article, “Why I Don’t Call Myself A Gay Christian.” This article launched Mattson’s career as one of the most visible spokesmen for Courage, until they parted ways in January.

The criticism which has frequently been directed our way, by Mattson and others who speak for Courage, is that by using the word “gay,” we were making our sexuality the defining aspect of our identity. We have explained that this is not our intent on numerous occasions (see below for further examples).

I recently read Courage founder Fr. John Harvey’s 2007 pamphlet, Same Sex Attraction: Catholic Teaching and Pastoral Practice [PDF], and thought the following paragraph shed valuable light on the rather absurd mentality behind Courage’s critique:

The time has come, however, to refine our use of the term homosexual. A much better term than “homosexual person” is the following: a person with same-sex attractions. The distinction is not merely academic. Instead of referring to “homosexual persons,” which implicitly makes homosexuality the defining quality of the people in question, we can put things in clearer perspective by referring to men and women with same-sex attraction. A person, after all, is more than a bundle of sexual inclinations, and our thinking about same-sex attraction (hereafter SSA) is clouded when we start to think of “homosexuals” as a separate kind of human being. “The human person, made in the image and likeness of God, can hardly be adequately described by a reductionist reference to his or her sexual orientation . . . every person has a fundamental identity: the creature of God and by grace, His child and heir to eternal life” (Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, Letter on the Pastoral Care of Homosexual Persons, 1986, no. 16)

This criticism illustrates, I think, just how radical Courage’s view of language is, and how far it has departed from the language of the Church itself.

Fr. Harvey’s first book on the pastoral care of “persons with same-sex attractions” was titled The Homosexual Person: New Thinking in Pastoral Care. I presume that he did not intend to implicitly make homosexuality the defining quality of the people he was ministering to. It’s fine, of course, if his own thinking had changed since 1987, when The Homosexual Person was published, and if by 2007 he preferred to talk about persons with same-sex attraction.

However, we are not just dealing with Fr. Harvey’s own language choices, but with an argument which implicates the language of the Church’s official documents. As the authority for his argument against the term “homosexual person,” Fr. Harvey cited the 1986 Letter to the Bishops of the Catholic Church on the Pastoral Care of Homosexual Persons, which uses the phrase “homosexual person” in the title and repeats it 22 more times in the body of the document. The phrase also appears in the title and body of Considerations Regarding Proposals to Give Legal Recognition to Unions between Homosexual Persons (2003) from the CDF, and in the body of Ministry to Persons with a Homosexual Inclination: Guidelines for Pastoral Care (PDF, 2006) from the USCCB. The phrase is also used in the Catechism of the Catholic Church (2359).

All of these Church documents were promulgated before Fr. Harvey published the paragraph above. Can he seriously have argued that in so many Church documents, the phrase homosexual person really “implicitly makes homosexuality the defining quality of the people in question”?

Part of the problem is an issue with the English translation of the 1986 Letter. An important section of the paragraph (which Fr. Harvey partially omits) would have been better translated:

Today, the Church provides a badly needed context for the care of the human person when she refuses to consider the person only as a “heterosexual” or a “homosexual” and insists that every person has a fundamental Identity: the creature of God, and by grace, his child and heir to eternal life.

Adding “only” to the translation agrees with the Latin original, as well as the German, Italian, Spanish, and Portuguese translations. Only the French translation agrees with the English in omitting “only” from the paragraph above. In terms of authority, the Latin text is the official text promulgated by the Church. German is the native language of Cardinal Ratzinger (later Pope Benedict XVI), the Prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith at the time the Letter was drafted and promulgated. And Italian is the most commonly used working language in the Vatican. So the agreement of these three languages is strong evidence that the revised translation better reflects the intended meaning of the document.

Had the English version of the Letter been clear—as the Latin, German, Spanish, and Portuguese versions were—that the Church does not consider the person only as a “heterosexual” or a “homosexual,” it might have been clearer that this paragraph should not be taken as a prohibition on referring to “homosexual persons,” but only to doing so in a reductive way.

The fundamental point, however, is not about words or phrases but about meaning. Spiritual Friendship writers have repeatedly asserted that we do not regard our sexuality (whatever that modern word means) as the defining quality of our personhood. But it’s not just that we do not speak precisely enough to satisfy Courage’s strange linguistic hobbyhorse: even Cardinal Ratzinger did not live up to Fr. Harvey’s exacting expectations about language!

Thinking about this focus on “same-sex attraction” versus “gay” reminds me of an incident that occurred back when I still attended Courage meetings. One day—quite unusually—we had two new visitors the same week.

One was a middle aged man. He told his story: he was married, but was compulsively cheating on his wife by hooking up with men. Everyone wished him welcome, said that he had a really tough struggle, and assured him that he would find welcome and support there. He became a regular member of the group, and continued to confess compulsive hook ups.

The other was a college undergraduate, from a very conservative family. He said that he was gay, but had never had sex and wanted to follow Church teaching. Immediately, the group challenged his use of the word “gay.” I spoke with him afterwards, and he expressed frustration with the way the group had lectured him about language. He never came back.

The first man, who was welcomed without challenge, was unquestionably engaged in habitual, sinful activity. I certainly don’t think it was necessary to immediately confront him with his sin—it might easily just push him away. But Catholic teaching is very clear about the sinfulness of cheating on one’s wife and of any sexual activity with other men.

Despite using the phrase “struggling with same-sex attraction,” the older man’s life was much more defined by his sexuality and the sinful habits he had formed around them. And despite using the word “gay,” the young man had done far more to resist allowing his life, choices, and habits to be defined by his sexual attractions.

Yet this was not the point that other members of the group felt needed to be made: the point that they decided to focus on was the undergraduate’s choice to describe himself as “gay,” despite saying he had never had sex and that he intended to follow Church teaching.

Remember, this was a kid from a very conservative background, and this was almost the first time he had tried to open up about his struggles in a Catholic setting. If it’s not necessary to shame the older man for adultery and sodomy, why shame a kid who’s trying to obey Church teaching for using a three-letter word, rather than a three-letter acronym, to describe his struggle?

I don’t fully understand Courage’s obsession with language. It may be that for men who have been sexually active, “gay” is more closely associated with sinful sexual activity, and “same-sex attraction” shifts the focus to attraction; whereas for those who have not acted on their attraction, “gay” is associated primarily with their experience of attraction. I also sometimes wonder if it stems from the fact that it’s easier to change the language you use to describe yourself than it is to break sinful habits and live chastely.

In the end, I don’t care much if someone else feels more comfortable with “person with same-sex attractions” and wants to use that terminology. As long as they are trying to promote an understanding of homosexual attractions and activity that follows the Bible and Catholic teaching, I regard debates about language as secondary (though I have made my own choices about language based on thinking fairly carefully about who I’m trying to communicate with and what I’m trying to communicate).

Different words communicate better with different audiences. I’m happy to describe myself as same-sex attracted if I’m speaking to a predominantly conservative audience and believe that doing so will communicate my meaning more clearly. But I think that particularly speaking to younger audiences—and many of the venues I have spoken at have been Christian colleges and universities—it’s easier to communicate by just saying I’m gay and celibate and talking about why I do that out of love for and obedience to Christ.

But in dogmatically asserting that everyone must use variations on “same-sex attraction,” Courage is not just criticizing the writers of Spiritual Friendship. It’s criticizing the language of the Church itself.

I’ve included a number of links to posts below which will help interested readers to clarify our thinking on language. It is profoundly saddening to me to survey all these posts, and consider how much effort we have had to spend clarifying the confusion spread by those who, like Fr. Harvey and Dan Mattson, had an unhealthy obsession with language. How much time and energy has been wasted, and how much unnecessary conflict created, by these futile debates about mere words and phrases!

More importantly, I have also linked to a number of posts that engage with—and attempt to understand and explain—Catholic teaching, including terminology like “disorder,” “disinterested friendship,” and the like. Ultimately, fidelity to the substance of Church teaching matters much more than the particular language we choose to make that teaching comprehensible to a particular audience (though language does matter for communicating substance).

Selected posts on language:

- Sexual Orientation: Is That Even a Thing? (Aaron Taylor)

- On Bilingual Pastoral Theology (Wesley Hill)

- Ontology and Phenomenology (Ron Belgau)

- What is “Gay”? (Ron Belgau)

- What “Not Reducible” Means (Jeremy Erickson)

- The Problem with Same-Sex Attraction (Ron Belgau)

- “Gay”: Clarity or Obfuscation? (Part 1) (Ron Belgau)

- “Gay”: Clarity or Obfuscation? (Part 2) (Ron Belgau)

- Whose Gayness? Which Homosexuality? (Aaron Taylor)

- Is It OK for Christians to Identify as Divorced? (Ron Belgau)

- This Is “Gay” (Chris Damian)

- This Is Me (Chris Damian)

- Gay Identity (Ron Belgau)

- Identity Questions (Ron Belgau)

- What is My “Identity?” (Jeremy Erickson)

- How to Evade the Real Issues (Jeremy Erickson)

- Once More: On the Label “Gay Christian” (Wesley Hill)

- Some Clarifications Regarding Sexual Orientation and Spiritual Friendship (Ron Belgau)

- And Again…More Thoughts on LGBT Terminology (Nick Roen)

- Label Makers (Matt Jones)

- Spiritual Friendship and Christian Ministry (Ron Belgau)

- One More Reason to Avoid “Gay”? (Wesley Hill)

Selected posts on Church teaching:

- “Always Consider the Person”: Homosexuality in the Family (Ron Belgau)

- Friendship and Catholic Teaching about Homosexuality (Ron Belgau)

- What Does “Disinterested Friendship” Mean? (Ron Belgau)

- Translating “Disinterested Friendship” (Ron Belgau)

- Intrinsically Disordered? How Not to Talk About Homosexuality (Aaron Taylor)

- Intrinsic Evil and Disorder: How To Misunderstand the Catholic Catechism (Daniel Quinan)

- Positive and Negative Precepts (Ron Belgau)

- LGBT Rights and the UN: What the Church Does Not Teach (Aaron Taylor)

- The Synod on the Family and the Pastoral Care of Homosexual Persons (Ron Belgau)

- An Incomplete Thought about Beauty and “Sexuality” (Ron Belgau)

- “Organic” Developments in Catholic Teaching on Homosexuality (Aaron Taylor)

I resonate with this. It seems exhaustive to ruminate over words and phrases. Within various contexts, I use “gay” and “same-sex attracted” interchangeably. In one instance, if I were to say same-sex attracted the other person could ask, “why did you say same-sex attracted and not gay; why did you make the distinction?” They may not understand why I used that specific terminology. I may be too tired to explain that distinction. I may have to go to an appointment in ten minutes. So, I’ll just use “gay” depending on the situation at hand.

In general, however, I do not refer to myself as “gay” or often say “gay-Christian”. I do not know anyone who says, “I am a heterosexual Christian,” or, “I am a straight Christian.” I am not any less of a whole person if I do not use that specific terminology. I mean, my whole person is being conformed to the image of Christ (2 Corinthians 3:18) and that includes all of the other ways I could identify myself.

I do not see what makes it morally impermissible to use the term “gay”. I think Paul made it clear that it is okay and necessary to contextualize (1 Corinthians 9:19-23).

Gay label critics suffer, I think, from a phobia. A phobia as a result of their wrong thinking that there is nothing redemptive about being gay. This is false and is throwing the baby out with the bath water!

Having a gay nature is rich in many ways among them having a sensitivity that others may lack. This allows for deep friendships with either gender but particularly with the same gender. Such same gender relationships can be rich and meaningful offering a model to ‘straight’ folk who often lack or worse are afraid to venture there. Many gay people possess an intensity not only in relationships but in their devotion and dedication to work and creativity. Much is redemptive in having a gay nature.

Gay label critics need to understand that the only not good aspect of being gay is danger of eroticism. Prevalent yes in the secular world, but those walking intimately with Jesus have a protection and a spiritual power to fight and overcome that temptation. Gay label critics need to find peace and understand why some see being gay as a gift that is redemptive by a God who allows it for His higher purposes.

I’m of the impression that the majority of these critics actually don’t believe in the logic of their arguments. One example: most of them find nothing wrong with comparing being gay to alcoholism, and I cannot recall hearing them use the phrase “someone who struggles with drinking” to identify the hypothetical person. I don’t think they have any problem using the world “alcoholic” as a descriptor for a person.

There also seem to be two different, but related, arguments these critics make: (1) don’t say “gay”, and (2) don’t say “gay Christian.”

The reason I identify these as different arguments is that often, the second point is made with examples such as, “I don’t call myself an alcoholic Christian” or “I don’t call myself an adulterous Christian” or something to that effect. Whereas they would probably have no problem using those adjectives to describe a person.

In fact, I would find it difficult to imagine critics to snapping back at someone who cheated on his or her spouse and who calls him- or herself an “adulterer.” I imagine that descriptor would almost be welcomed as a sign of healthy recognition of one’s sin.

The issue then is not the word “gay” in itself, or even the idea of using it as a descriptor. The reason they keep repeating the same arguments about ontology is because they don’t actually believe them.

Rather, it’s the fact that the word “gay” does not have negative connotations. They accuse those who use it as “identifying with their sin,” whereas it’s precisely the opposite. To use a phrase such as “struggles with same-sex attracted” is to place a focus on one’s weakness, and, in a small way, to humiliate oneself before the person he is speaking to. When I use to use that term, I dont recall ever saying it in a spirit of matter-of-factness or joy. It was always associated with a certain shame about myself, the way things were, the state of the world, etc.

To use the phrase “struggles with same-sex attracted” is to identify, therefore, with one’s shame and affliction in a way that satisfies their desire to maintain the hierarchical relationship between heterosexuality and homosexuality.

Using the word “gay” by definition creates a relationship of equality by enforcing, inherently, the concept of sexual orientation and the belief that there are different but equal forms.

This threatens their own identity but because they don’t realize that, they just use the same arguments, over and over and over again, because they themselves aren’t satisfied by them.

It’s a huge waste of time, because no one seems to be addressing the real issue of their psychological motivations.

I have a few more thoughts since talking with a friend yesterday about this post.

1.) While driving into Minneapolis one day, I observed multiple billboards that hallmarked mostly women fixed in erotic positions sometimes with men and barely dressed posing for major clothing brands. That is normal. I drove by barely noticing the first two until I saw the third one and I thought, “This is absolutely incredible how I am so desensitized to soft-core porn on a billboard.” What if those billboards were plastered with two men, fixed in erotic postures and barely dressed? That may be a little more striking—and I am not saying that because I am merely at a disposition regarding same-sex attraction. I would imagine that statistically, the responses to billboards like that would be much more excited. So, what I am saying is that, homosexuality is not normalized in the sense that it is commonly accepted or even fully understood in the modern world. I will restate what others have said—the concept of sexual orientation and identity is relatively new. At this point, there does not necessarily seem to be a stable definition for sexual orientation—at least in regard to a socio-cultural context which includes all of the thoughts and attitudes of a society’s participants. What I am not saying is that I would endorse billboards that display two gay men posing erotically or even billboards that display women posing erotically. In reference to Mike H’s comment–“using the word ‘gay’ by definition creates a relationship of equality by enforcing, inherently, the concept of sexual orientation and the belief that there are different but equal forms–I think this is rather significant in acknowledging our own experiences and that of others and I am sure for persons who were born prior to the millennial generation the manner to which homosexuality is being normalized is a shock. It is, indeed, a culture shock.

With that, I would consider some critics’ thoughts as noble because some if not most of them recognize that there is, in fact, the existence of an idealized order to creation. Guillaume Groen van Prinsterer shares some insight into this stating:

“The created order for reality, which encompasses both the natural and moral realms, represents God’s will for life and invites man to follow it in joyful obedience and humble submission, but which also brings retribution when denied or defied. Thus, it is an order which cannot be ignored with impunity and which explains much of the misery and friction in the life of mankind.”

I do not mean to protect malice behaviors in whatever ways they manifest but I think it is important to validate the integrity that underlies some of their intentions. We live in an age where the order of creation is being challenged perhaps exponentially which can be unnerving for many people when seeking to make sense of the obvious dissonance between a rapidly changing culture and the original intent of our Creator over all of creation which is not limited to the sexual dimension of the human created order. In many ways, broadening the categories for sexual orientation and accepting them as real experiences creates tension that could be most similarly described as a struggle against relativism and the potential consequences that has not only for the church but for the world at large.

2.) When encouraging others not to use “gay” or “gay Christian” seems to infer that being “gay” could somehow be represented as a stable identity. But then, how is being “straight” a more stable identity? By that thinking, we should, in fact, assume then that both ways to identify are, therefore, stable. I really liked Jon Evan’s comment so no disrespect but there does not seem to be any redeeming quality inherent to any sexual orientation but only in the way Christ is redeeming our sexuality–and in Christ we have been brought to fullness (Colossians 2:9-10).

3.) Something else that I have noticed amidst all of these conversations is the assumption that identifying as “gay” could interfere with the power of God’s Holy Spirit to cause an orientation change. This phenomenon has often confused me. “Why do others experience transformation in their orientation and others do not,” I would ask God? Almost always the reply pointed to God’s sovereignty and even then it still did not make complete sense. I realized at one point it was not necessary to experience a change in sexual orientation. I guess I trust in God’s oversight and provision for me as a laborer. It is simply not required. Jon Bloom wrote about God’s sovereignty in a different way:

“The cessationism-continuationism debate is also a moot issue for them. They regularly see the Holy Spirit do things we read about in the book of Acts. As my friend described the Spirit’s activity where he lives, it was clear that all the revelatory and miraculous spiritual gifts listed in 1 Corinthians 12–14 are a normal part of life for these believers — because they really need them.”

The only connection I make between these simply deal with the miraculous by definition and, specifically referring to the spiritual gifts, “he distributes them to each one, just as he determines” (1 Corinthians 12:11). This would strongly suggest that the same God who is sovereign and determines who gets what revelatory and miraculous gift also determines who experiences a miraculous orientation change both for the believer and the advancement of the gospel.

It was Carl Jung who pointed out that gay is distinctive beyond the same sex attraction. There is more to gay which isn’t so obvious to many straight men.

Carl Jung identified the archetypal gifts of gay: “a great capacity for friendship, which often creates ties of astonishing tenderness between men”; a talent for teaching, aesthetics, and tradition (“to be conservative in the best sense and cherish the values of the past”); “a wealth of religious feelings, which help to bring the ecclesia spiritualis into reality; and a spiritual receptivity which makes him responsive to revelation.”

There is much here that is good and distinct. To be celebrated and I for one have gained much solace from these insights.

This is such an excellent piece, THANK YOU! I am bookmarking it to share and forwarding it to friends!

I don’t recall reading this entry, but I agree wholeheartedly. I went through years of mental gymnastics and interior dialogue over this issue. I’ve found Spiritual Friendship writers especially helpful in this matter.

Scared away at first by conservative writers who said you can’t be Catholic and be gay, or you can’t say this or that, and you can’t live with another as brothers instead of lovers, I tried to make sense of their interpretation of Catholic Teaching on the subject. As you point out, their ‘doctrine’ was stricter than what the Church actually taught.

I ascribed to the Courage ‘requirements’ of language, but found it awkward and incredibly disingenuous. Friends and family would say, “WTH? You aren’t gay?” It was very difficult and frustrating to try and explain that to those who knew me. Until Pope Francis came along, when I was able to function, to breathe with a greater freedom of spirit.

I think, for many, the banner, ‘Courage is the only approved apostolate for the SSA in the Church’, as well as the veneration many of us have for Fr. Harvey, probably accounts for our reluctance to fall out of step, as it were. The emphasis on terminology can lead to a certain scrupulosity, as well as a kind of prejudice towards those who are more comfortable with saying ‘gay’. The language issue – or the insistence of not using the term gay or homosexual, seems to be influenced by the work of Dr. Nicolosi and the promotion of reparative therapy/conversion therapy as a ‘way out’ of a ‘lifestyle’. In the late ’80’s I went through therapy – finding it helpful in self-knowledge and understanding my early childhood experiences, but it wasn’t helpful as a means to change sexual attraction. I started out with an Evangelical psychologist and later switched to a secular therapist, who specialized in sexual addiction.

Anyway – I’m old now, and so many of these arguments seem to end up causing greater confusion and often present roadblocks to healthy spirituality and personal development. Having said that, keep up the good work Ron.