In the last half century, no psychological theory has had as much impact on our knowledge of adult love and relationships as attachment theory. By looking at a person’s relationship with her or his parents and how he or she handles stress within the relationship, attachment theory brings insight to some of the unconscious ways that humans relate to other humans and helps to explain ruptures and disconnections.

At the end of 2016, Christine Baker published a study on celibate gay Christians revealing this population’s common attachment styles — how a person handles stress within their closest relationships. Using the four categories of attachment styles including secure, ambivalent/preoccupied, avoidant/dismissive, and fearful/avoidant, her findings show that celibate, gay Christians experience far more anxiety in their relationships than the general population. This anxiety often leads to poor views of one’s self and contributes to a lot of insecurity within relationships.

In this blog series on gay men and falling in love (see Part 1 here), understanding attachment theory and the insecure ways that people tend to relate to their attachment figures will greatly help us think about the ways that we approach falling in love.

Here’s how the attachment system works in adulthood.

At any given time, we need a handful of people who serve as attachment figures for us. An attachment figure is not just any friend or any social relationship. These attachment figures are people to whom we turn when we’re anxious and who provide us with emotional stability so that we can go back to exploring our world. And, despite the prevalence of attachment literature on romantic relationships, some friends can and do serve as attachment figures.

When there is no stress, our relationships with our attachment figures are solid. We enjoy them, we feel safe around them, and we can feel free to pursue our work. When stress hits, we seek them out to be comforted by them. If they are unavailable, inattentive or unresponsive, we experience attachment insecurity and work within our attachment styles to deal with that anxiety.

Unfortunately, as we will see, our anxious proximity-seeking behaviors or anxious avoiding behaviors often leave us with more anxiety, frustration, and broken relationality. Even though we’re seeking comfort, we engage in behavior that further compounds our fear and frustration and distances us from intimacy with our attachment figure.

Let’s take a look at these attachment styles:

As a quick note, these styles exist not simply in category format but on a spectrum. One might find herself or himself resonating with parts of a style but not feel fully committed to it. These styles are more for insight, and if parts don’t resonate with the reader’s experience after evaluation, she or he should simply discard them.

Bartholomew, K., & Horowitz, L. M. (1991). Attachment styles among young adults: A test of a four-category model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 226-244.

Secure

Adults who demonstrate a secure attachment style are not happy all the time nor do they experience perfect relational harmony. They experience disconnections in their relationships, frustration at their attachment figures, and fears and anxieties about the future; however, they tend to believe that their attachment figures will be there for them when they need them (low anxiety) and when stress does hit, they run to their attachment figures for comfort (low avoidance).

People with a secure attachment style have a positive view of self (“I am worthy of love and affection”) and a positive view of others (“Others are willing and able to love me”). They were showed love and affection at an early age and thus believe that people will generally be there for them. When they experience anger, the anger is loving anger for the sake of the relationship. They communicate their anger to express their hurt and to better understand their relational partner but not to harm him or her.

People with a secure attachment style still must grow in intimacy and must grow to understand and relate to their significant others but can generally do so without self-sabotaging by running away or by exploding in anger.

Preoccupied/Ambivalent

Adults who demonstrate a preoccupied/ambivalent attachment style tend to have a low view of self (I am not worthy of love and affection) and a high view of others (others are capable of loving me but may not because of my faults). While they do the positive work of seeking proximity during times of distress, they tend to have high anxiety about the stability of their relationship. The common refrain that runs through the minds of people with the ambivalent attachment style is “I will always love them more than they will love me.”

The word ambivalent comes from the propensity for these adults to vacillate very quickly between heavy idealization (“You’re the most amazing friend in the world!”) and a spiteful demonization (“You never loved me or cared about me!”). They then engage in behaviors that either involve heavy proximity-seeking such as excessive communication, wanting to socialize all the time, or this constant need for reassurance about the state of the relationship or involve punishing behaviors such as passive-aggression, criticism, or stonewalling — shutting down the conversation and refusing to talk to the other person.

The preoccupied part of this attachment style comes from the fact that these adults tend to find themselves constantly thinking about their attachment figure because they’re stressing out about the security of their relationship. Thus, not only do they find themselves preoccupied constantly with what their significant other is doing but they are also always looking for signs that their significant other will abandon them. Upon any sign of perceived abandonment, their anxiety levels skyrocket, and they begin either proximity seeking or relational punishing.

One of the deepest insecurities for these adults is being seen as pathetically unlovable and one of the deepest dreads is being abandoned. It’s unfortunate because in an effort to stave off abandonment, they frequently engage in behaviors that push people away.

It’s important to highlight here that these adults are not crazy and are not making up disconnections. Small things like showing up late for meetings, failing to keep a promise, working too much, or consistently misunderstanding someone can feel chasmic to the person experiencing the hurt. And because hurt can compound itself, adults with an ambivalent attachment style may find themselves beginning a conversation hoping to express hurt in a calm, calculated manner but ending it with screaming and yelling.

For these adults, their focus must be on coping with their anxiety levels around the security of the relationship, communicating their deep expectations about the relationship (that they may feel intense shame about), and seeking to restore connection when it is lost.

For those in relationship with these adults, their focus must be on providing a space for emotional expression, limiting defensiveness, and validating the other’s emotional experience as well as maintaining good boundaries.

Somewhat paradoxically, an adult with an ambivalent attachment style tends to attach to an adult with an avoidant attachment style because each affirms what the other thinks about him or herself.

Dismissive/Avoidant

Adults with the dismissive/avoidant attachment style tend to have a high view of self (“I am the only person I can trust to get my needs met”) and a low view of others (“Others are unwilling or incapable of loving me”). While they tend to have low attachment insecurity believing the other will always be there for them, they also engage in high avoidance attempting to solve their stress on their own. The common refrain that runs through the mind of these people is “I can’t trust anyone and cannot show weakness.”

The word dismissive is used because these people tend to dismiss their emotional states. They view the darker emotions like sorrow and fear as a sign of weakness. They reflexively bury their emotions and are often unaware of their emotional states. They also tend to disavow their emotional states often blaming others for being too sensitive or needy. This dismissal of emotion does not remove it so these adults are likely to have periods where the emotion catches up with them and overwhelms them.

The avoidance moniker comes from this style’s tendency to avoid emotional intimacy. When stress hits, instead of moving to their attachment figures for comfort and support, they tend to bury themselves in their work. This doesn’t mean that these people are all introverts. On the contrary, many can be very personally charismatic and may have a lot of surface-level friendships. However, once someone gets through their armor, alarms go off and they quickly distance themselves. This distancing includes not only proximity but also emotional distancing. They may talk down the relationship or talk up other relationships as just as close and intimate as the attachment relationship.

What is often difficult in relating to adults with avoidant-dismissive attachment styles is that because they don’t express emotion readily, they’re sometimes harder to relate to. Add in their tendency to talk down the relationship during times of peak stress, they come across as robots or emotionless jerks. However, as we understand from Ainsworth’s study, they’re experiencing just as much emotional distress as the preoccupied type but simply cannot express it.

What is vitally important is that underlying this attachment style is a deep-seated dread that if anyone ever got through their armor, they would actually find nothing of value. Adults with an avoidant attachment style may throw up seemingly impenetrable walls but their deepest insecurity is that they, too, will ultimately be rejected. They use avoidance to distance themselves because they are so unsure of who they ultimately are that they fear losing their identity in relationships. This means that they tend to interpret secure levels of intimacy as clinginess.

For these adults, their focus must be on leaning into relational discomfort, sharpening their intuition to notice when their significant other is negatively affected by their behavior, and expressing and negotiating healthy relational boundaries to establish more firmly their sense of self.

For those in relationship with these adults, their focus must be on validating emotion and perspectives when they’re expressed, remaining firm in their own relational needs, and being patient with those they love who avoid. It will also be helpful to add relationships outside of this one to provide more emotional stability when the attachment figure is avoiding.

Disorganized/Fearful

Adults with the disorganized/fearful attachment style tend to borrow from both the dismissive/avoidant and preoccupied/ambivalent attachment styles. They have both a low view of self (“I am not worthy of love and affection”) and a low view of others (“Others are unable to meet my needs”). These adults are frequently victims of intense trauma and having had their core assumptions about the world shattered from their trauma, are left feeling a chasmic divide between them and those around them.

Trauma does not necessarily mean abuse or death. Being a minority like being a gay woman or man in a family and/or community that demonizes and ridicules a gay identity can be long term daily trauma that convinces a person that she or he is not, to use Heinz Kohut’s phrase, a human among other humans.

This word disorganized arises from the inability of these adults to organize their experience and their relational networks. They often fluctuate between unbearable clinginess (the hyper activating behaviors of the preocuppied/ambivalent style) or icy avoidance (the deactivating behaviors of the avoidant/dismissive style).

For these adults, their focus should be on working through trauma and feeling through their stories, and for those in relationship with them, their focus should be on hearing and validating stories while maintaining good boundaries. Trauma survivors typically need a trained clinician who can make space for their emotionally difficult stories and help them process through their emotion in a safe way.

Let’s return to Baker’s study.

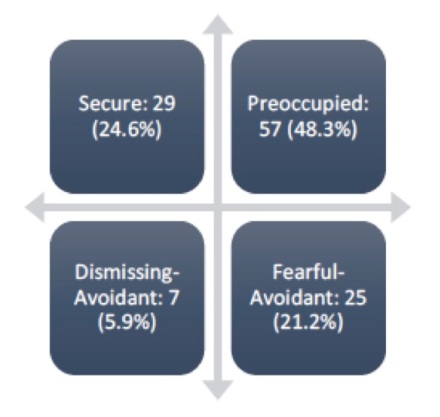

Baker provides us with the following percentages for gay celibate Christians and their attachment styles:

As stated earlier, these numbers are skewed toward anxious attachment with most estimates of the general population having higher numbers of secure and dismissing-avoidant styles and lower numbers of preoccupied and fearful-avoidant (disorganized) styles. Even acknowledging her number of participants, this data shows about 70-75% of this population as having an insecure attachment style.

This means that a large portion of gay celibate Christians tend to have high attachment anxiety — an anxiety marked by a fear that they will always love their attachment figures more than their attachment figures will love them, a dread of abandonment and disconnection, a deep desire to be around their attachment figures at all times, and a constant preoccupation with thoughts of that person.

As we’re thinking about gay folks and falling in love, we can begin to see how some of these normal attachment styles play into our adult relationships. Instead of pathologizing their desires to be around their friends as solely sexual or wickedly evil, gay celibate Christians can reframe their relationships as desiring security and comfort yet engaging in maladaptive behaviors that limit those goods. The energy then shifts from denying anthropological realities to relieving anxiety by ordering loves.

There are many contextual and cultural factors that play into how gay men specifically experience their attachment relationships. In the third post in this series, I hope to explore more of those particularities.

This is really helpful. These ways of coping are not best understood as sin patterns or evil but as unhealthy. Automatic responses I learned in childhood that no longer serve me. When I was a child I thought as a child. Oddly one of the reasons I have avoided the term gay is I identify these insecure attachment styles and endemic to the gay community. As I sought to overcome them it has helped to no longer think of myself as gay since I associate these ways of relating with the way I see gay men relating to one another particularly in their romantic relationships.

Pingback: Gay Men and Falling in Love – Part I | Spiritual Friendship

Excellent explanations. I can definitely see myself in the Preoccupied category. I wish I had read about this sooner. It helps explain some of the difficulties I feel personally, and also explains some of the difficulties I have with a very close friend.

Pingback: I Just Need To Write | stay strong sojourner

This definitely reflects some of my own experience when I was a younger man. I am much more secure today than I was in my 20’s and 30’s. I guess marriage and raining children has changed much of that.

Reblogged this on gudgerblogdotcom and commented:

http://www.derrickgudger.com

As the way we say in Brazil: Spoken, Spoken and didn’t said nothing.

Pingback: Gay Men and Falling In Love – Part III | Spiritual Friendship