God doesn’t promise that He’ll only ask you for the sacrifices you agree with and understand. – Eve Tushnet

The nuns taught us there are two ways through life: the way of nature and the way of grace. You have to choose which one you’ll follow. Grace doesn’t try to please itself; accepts being slighted, forgotten, disliked; accepts insults and injuries. Nature only wants to please itself. – Terence Malick, Tree of Life

In paragraph 265 of Amoris Laetitia, Pope Francis teaches:

We have to arrive at the point where the good that the intellect grasps can take root in us as a profound affective inclination, as a thirst for the good that outweighs other attractions and helps us to realize that what we consider objectively good is also good “for us” here and now. A good ethical education includes showing a person that it is in his own interest to do what is right. Today, it is less and less effective to demand something that calls for effort and sacrifice, without clearly pointing to the benefits which it can bring.

The basic message is traditional. Morality involves rational pursuit of the good. This is so by definition because humanity was created with a desire for happiness (which, as St Augustine beautifully explains in his Confessions, can ultimately be satisfied only by God) – or, as ancient Greeks called it, eudaimonia (“flourishing”). Whatever we choose, we choose because we judge, rightly or wrongly, that it will contribute to eudaimonia. As Herbert McCabe puts it:

Living well means doing good because you want to do it, because you have become the kind of you that just naturally wants to do this.

The Church believes her rules surrounding sexual behaviour are not arbitrary. The goods indicated as desirable by Church teaching are (in the Holy Father’s words) good “for us,” given the way our nature was created. Pope Francis is restating the Church’s belief that her teachings on sex concern natural law, not eccelesiastical policy.

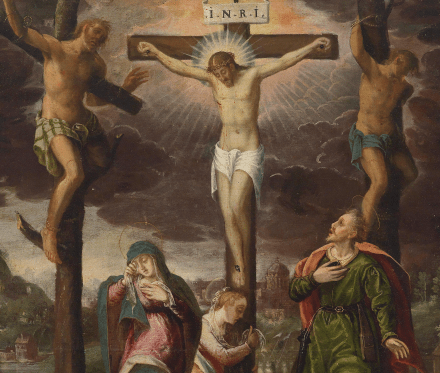

But paradigms of moral behaviour in Scripture often cannot be understood within the context of an ethic solely focused on the pursuit of eudaimonia. In the Garden of Gethsemane, Christ prays:

Abba, Father … all things are possible for you. Take this cup from me. Yet not what I will, but what you will. (Mark 14:36)

Christ, God and man, had two wills and two intellects (human and divine). His prayer indicates the desire of his (human) will is at odds with the Father’s desire. This suggests that Christ’s human intellect, in itself, could not grasp that his Passion was “in his own interest.” If it had grasped this, even his human will would have desired to undergo the Passion, since the will naturally desires what the intellect grasps as good.

St Augustine says that by praying as he did, Christ “shows Himself to have willed something else than did His Father.” St Thomas Aquinas explains this by arguing that although Christ’s “will as reason” always “willed the same as God,” in his “rational will considered as nature, Christ could will what God did not.” What is important to note is that even the human will of Jesus, although it never experienced disordered affection, cannot be said to have had a “profound affective inclination” toward his proper good at all times; nor can his human intellect, in itself, have been capable of completely comprehending that good, even though Christ’s human intellect (unlike ours) knew everything possible for a human intellect to know.

Then there is Abraham’s sacrifice of Isaac, presented in Scripture (Heb 11:17-19) as a pre-eminent moral example. Fr Andrew Pinsent writes:

Abraham … has to trust God, an action of second-person relatedness, despite the utter impossibility of attaining the desires of his heart according to any conclusion based on first-personal reasoning alone. This situation is therefore radically different in kind, and not in degree, from any scenario in which one sets out one’s own path for the attainment of one’s desires … Although the case of Abraham is an extreme one, to say the least, the story draws attention to a narrative that is more broadly applicable and can be experienced in more commonplace matters of daily life. A child, intent on attaining or holding onto what she desires, will often struggle to “let go,” to surrender to the will of a loving parent regarding some course of action that is for the child’s own good.

“First-person” morality (in Pinsent’s terms) means morality as the pursuit of our own good. This is crucial to the moral life, since it is the foundation of our ability to will anything at all (even willing to obey God).

But pursuit of the good needs to be set within a broader context of “second-person” relatedness. The parent has a more adequate grasp of “the child’s own good” than the child himself. To develop morally, the child must be drawn out of himself through a relationship of trust with the parent, involving the sacrifice of the child’s own will.

As with child and parent, so with man and God. And if, as Augustine and Aquinas suggest, this was part of the moral life of Christ as man, we should not expect to escape the necessity of such sacrifice. Christ taught that the moral life involves imitating his Passion (Matt 16:24), and his final words to St Peter contrast the immaturity of following one’s own desires with the spiritual maturity of allowing oneself to be led “where you do not want to go” (John 21:18).

Given that there are aspects of the good that we cannot grasp in a “first-person” manner, Christian morality is likely to be distorted by overemphasising the need to explain moral obligations in terms of their “benefits.” For example: in a social context which places high value on sexual pleasure and sexual variety, and encourages divorce when spouses “fall out of love,” we might expect to see exactly the sort of soft-pedalling of Christ’s teaching on adultery (Mark 10:11-12) that has become popular in the wake of Amoris Laetitia. After all, it is difficult to explain to a divorced Catholic in a stable and loving second union how following a teaching that requires them to give up a sexual relationship with their new partner is in their “own interest.”

The same dificulty would also extend to those in same-sex relationships. For instance, the midterm report of the 2014 Synod (which gave rise to Amoris Laetitia) says:

Homosexuals have gifts and qualities to offer to the Christian community … The question of homosexuality leads to a serious reflection on how to elaborate realistic paths of affective growth and human and evangelical maturity integrating the sexual dimension … Without denying the moral problems connected to homosexual unions it has to be noted that there are cases in which mutual aid to the point of sacrifice constitutes a precious support in the life of the partners. Furthermore, the Church pays special attention to the children who live with couples of the same sex, emphasizing that the needs and rights of the little ones must always be given priority.

Much of the commentary on the report was unhelpful. Hardliners boiled with rage over the claim that homosexuals have “gifts” (as if the Church had previously taught that gays are completely devoid of good qualities).

The disturbing thing about the report, however, is not what it says but what it did not say. It moves seamlessly from talking about “realistic paths of affective growth” to same-sex unions and child-rearing, with no mention of continence or celibacy. Built in to the report, it seems, is the assumption that no gay person in their right mind would attempt to follow Church teaching, and therefore the height of “human and evangelical maturity” that can be expected of gay Catholics is to live in sin while maintaining a vague connection with the Church.

There are various explanations for how this assumption ended up in a Vatican document. Undoubtedly, pastoral pleasantries are sometimes used as stalking horses for radical doctrinal change. But part of the problem lies with an overemphasis on morality conceived solely as pursuit of the natural good. As with the divorced and remarried, it is difficult to explain to gay people why following Church teaching is in their “own interest” (especially in a post-Obergefell milieu). If one thinks of morality exclusively in these terms, one is likely either to give up making the case for the Church’s teaching, or to distort its pastoral application (for instance, suggesting that it may be “impossible” for people to pursue chastity, but they should just receive the sacraments anyway).

To be clear: I am not saying that the Church should give up trying to articulate rational, natural law-based arguments for her teachings on sex. As Pinsent’s first-person/second-person analogy illustrates, God does not desire arbitrarily that we be chaste. He desires it because it is our natural good, desirable to a righly-ordered will. That means, the naturalness and desirability of chastity can, in principle, be articulated.

But who – straight or gay, married or single – has a perfectly rightly-ordered will? Even when natural law-based arguments convince in the absence of a prior faith commitment, they do not provide the grace necessary to live out what the argument proves. The most fitting foundation for the reception of this grace is, I would suggest, re-emphasis on a Christian spirituality of sacrifice – a spirituality which reminds us that there is a broader context within which the pursuit of our own natural good must be situated, namely, a second-person relationship with a God who calls us to be his friends.

Your thinking here is full of beautiful reflections of what it means to be filled with the grace of God in Christ.

Beautifully articulated and written.

“But who – straight or gay, married or single – has a perfectly rightly-ordered will?” And that’s our human weakness as Romans 7 so elagantly plumbs!

For the longest time I would plead for power to enhance my will. But it never arrived.

It’s because as you say it’s grace we need and power comes as we walk in intimate relationship with the All Powerful One who Himself overcame and is able to help those who walk in complete trust and surrender.

If the naturalness and desirability of celibacy for gay people can be articulated, why do you make no attempt to do so?

All I see in your words are variations on a theme of « God says so, therefore you must obey, or else ».

It’s immaterial whether that « or else » is hellfire and damnation or unhappiness and dissatisfaction in this life. If you can’t articulate a cogent and convincing case for either alternative then you have no argument. Or rather, your only argument is the argument from blind obedience, which to someone who doesn’t believe in your god is no argument at all.

When a Christian of your ilk exhorts me to sacrifice my sexual and relational expression on the smoking altar of a faith I do not share, and to my question of « why, exactly? », merely answers « because it says so in the bible », should he be surprised when I roll my eyes and move on?

To play the devil’s (or God’s, in this case) advocate this site and its posts exist to appeal to more conservative Christians. I also don’t find them very personally convincing and only really comment when I see something more generally abhorrent in the comments or post itself but for those of us who either don’t believe in God (or, in my case, I am more agnostic but have no reason to believe God is actually good or moral in its actions) these arguments won’t convince us much. I do agree with your view of Aristotelian natural law, though. Virtually everything Aristotle taught was pure drivel in my view. Inferior philosophy from an inferior proto-philosopher.

The author did actually articulate a theological argument for “the naturalness and desirability of celibacy for gay people.” I think that there is here an argument, suffused by the grace of God, for that very thing. It may need a believing heart to understand it, however, and I pray you come to a time in your life when you can see with new eyes what it means to believe in and follow God in Christ, with a knowledge of what a renewed naturalness is through him.

Ah, you mean his reference to the odd philosophy Christians call “natural law”?

My understanding of “natural law” is that it attempts to attribute moral worth to behaviours based on perceived benefit or detriment. Christians use it to condemn homosexuality on the basis that homosexual acts are detrimental to human well-being.

Problem is they’re not. Or at least, no more so than heterosexual acts. Indeed significantly less. Straight sex often leads to childbirth, and childbirth has a ravagingly detrimental effect on the human body. Gay sex doesn’t give you vaginal prolapse and deep vein thrombosis. It doesn’t require you to be sliced open in order to deliver a child who, if born in the usual manner, will kill you. It doesn’t lead to the septicaemia that killed millions in the days before modern medicine and still kills thousands of women in developing countries. And while gay sex may give you an STD, straight sex can do exactly the same.

No, it’s straight sex the Church should ban if it’s following the precepts of “natural law”. But it won’t, because that would defeat the purpose of appealing to it. The real purpose of “natural law” is to pathologize gay people and make us out to be unnatural. It’s a club designed to beat us into submission. Nothing more.

Of course as far as clubs go, it’s a pretty ineffective one. Only the most gullible and self-loathing among us can be persuaded to let themselves be beaten up by it. Swing it at most of us and you’ll soon feel it connecting with your own skull.

I mean, if I should swear off gay sex because of any danger it might expose me to, how much more urgent is it for your wife to swear off straight sex because of the far greater risks she’s taking? Declare yourself celibate immediately Mrs Wilson! Don’t let that husband of yours anywhere near you! All he’ll bring you is a world of pain and physical harm.

I already knew you weren’t reading the article as it was written nor following the reasoning that is in it since you weren’t showing any signs of sensitivity to the actual content nor the grace evident in it. So, I can only once again pray that you may some day be impacted by God’ Spirit and obtain a new perspective on these aspects of life you believe you understand already. Grace and peace to you.

What Mr Wilson really means in his comment above is that I disagree with the Christian assertion that homosexual acts are contrary to any kind of justifiable objective morality and that my disagreement proceeds from ignorance.

His response to me can be translated from Christianese into plain English as follows:

« I know better than you but I don’t feel obliged to explain why. I simply require you to understand that my superior knowledge needs no explanation. If you refuse, then although for form’s sake I’ll publicly state that I pray for you to recognize that whatever I say is the absolute and incontrovertible truth regardless of any evidence to the contrary, if you won’t, then the devil take you. »

Welcome to the wonderful world of Christian « love ». With friends like Christians, who needs enemies?

Ya know, I’m thinking that putting words in other persons’ mouths isn’t dialogue nor even critique but actually simple yet deliberate misrepresentation. If you can’t be fair and honest in your communication you may have issues that can’t be addressed conversationally. Are we done here?

Conversations with Christians always follow the same pattern.

First an appeal to biblical authority by the Christian.

When the non-believer explains that for him the bible is no more authoritative than any other book (eg. the Qur’an, the Nihon Shoki, the Silmarillion…), the Christian then trots out « natural law ».

Ah, « natural law ». That embarrassingly amateurish and desperate mix of faith, prejudice and pseudoscience. Good for a laugh even if its persistance in a world where we’re taught to think critically does make one despair at the power of hatred and superstition to triumph over the logical mind.

Still, once the non-believer has stopped laughing (or crying) and proceeds to blow the fallacious arguments of « natural law » out of the water, the believer is then backed into a corner where he has two choices. He can either abandon his faith (which happens surprisingly frequently) or he can stick his fingers in his ears and shout « I know I’m right! I know better than you! May god forgive you! ».

That you have made the second choice is evident enough. But the fact remains that just because you say something doesn’t make it true. Unless you’re god, of course.

Are you? Am I conversing with the creator? If so, and you can provide me with reasonable proofs of your divinity (you know, like Christ is supposed to have done via miracles and coming back to life and all that sort of thing), then I’ll be forced to believe you. If not, you’re just another ordinary human, and why should I listen to you?

If you have arguments to advance, advance them. If you don’t, then you’re quite right. This conversation is at an end.

You get the last word

Now I do.

How much bitterness…

Ah, bitterness!

That emotion that only the victims of the hatred of Christia

As I started to say above…

Ah bitterness!

That emotion that only the victims of the hatred of Christians feel. Well, according to Christians, that is.

Is bitterness a sin? And if so, why is it sinful for me to feel bitter because of the centuries of hatred heaped by Christians on people like me, whereas it apparently isn’t sinful for Christians to feel bitter about losing the public debate over equal marriage?

If you want to see real bitterness, check out any conservative Christian website. Especially Australian ones at the moment. Now there are some sour grapes of the most wince-inducing variety…